Nota inicial: após uma troca de emails com o escritor Misha Zaslavsky, acrescento alguns dos seus comentários (em inglês) ao meu texto, assim como mais umas informações abaixo. O texto foi ligeiramente editado.

Apesar da Rússia ter as suas próprias tradições de narrativas com ou pelas imagens, creio que este livro é feito já num contexto de maior mundialização da banda desenhada. Se bem que, face à pergunta, “conhece Breccia?”, os autores em questão possam responder negativamente, a obra em si avançaria um assertivo “sim!”. [The authors answer “yes”. In the time of working on M&M, we had seen Breccia’s Perramus and some of his shorts. In addition, as far as I can recollect, Akishin had had in his influential background Alex Toth, Kirby, Wally Wood, Pratt, Munoz, Sergio Toppi, and a huge number of graphic artists besides comics.] Os caminhos podem ser multímodos e indirectos, como a luz reflectindo-se nos espelhos ou noutras superfícies antes de chegar ao último destino, aquele que observamos no momento presente. Compete ao crítico aperceber-se dessa rota da luz, retrospectivamente, e adivinhar qual a luz que brilha na origem, de onde emana ela, não para fazer filiações taxativas e inertes, mas estabelecer relações de familiaridade.

Porquê Breccia face à adaptação de Le Maître & Marguerite, romance de Mikhaïl Boulgakov (que teve uma edição portuguesa pela Contexto), de Misha Zaslavsky e Askold Akishine (autores que, de resto, me são totalmente desconhecidos)? Porque não McKeever, se também com este autor norte-americano partilham tantos pontos de contacto gráfico – manchas de tinta pairando em torno das personagens, uma escolha dramática por perfis, recortes em contra-luz, em negativos, em silhuetas, uma profusão de “ruído” gráfico adensando os ambientes, mesmos os mais iluminados, por corpos relativamente estilizados e uma escolha oscilando entre faces extremamente caricaturizadas e outras mais suaves, mais humanas (revelando, obviamente, uma escolha de “moralidade” e de “valorização” das mesmas personagens) - ? Porque não outros autores? Para além desta ser uma questão retórica, é também sem resposta, pois o que importa é apercebermo-nos da susceptibilidade, da potencialidade, da eventualidade dessas ligações, e não da sua perene e inabalável exactidão.

Mas tentarei explicar por que razão elegi Breccia neste caso particular, para um objecto tão distante em todos os aspectos do trabalho do argentino. Em primeiro lugar, pelas características visuais que acabei de citar, apesar de por um desvio por um outro autor, norte-americano (e poderia citar outros, nesta contínua associação de características, nesta possível emergência de uma história livre). Depois, pela natureza da adaptação. Sendo incomportável uma adaptação de todo o romance, ou indesejável uma sua absurda redução – perigo no qual ocorre desde logo toda e qualquer “adaptação” – optaram os dois autores (será que o tratamento algo diferenciado das personagens, que indiquei, se deve às quatro mãos em separado? Ou os autores tocam mesmo a quatro mãos? – na verdade, “a duas”, pois só Leonardo é que desenhava com as duas ao mesmo tempo) então por dramatizar na sua banda desenhada episódios-chave, significativos, metonímicos da força perene da obra de Boulgakov (a relação dos quais está feita no prólogo Michel Parfenov). [ Definitely, It was one hand – the Askold’s one. I only worked with text.]

O livro original fez furor aquando da sua tardia descoberta no seu país de origem, em Portugal durante uma fase em que se publicavam grandes clássicos (e grandes barbaridades) das letras soviéticas. Esta adaptação não me parece decidir-se pela extrapolação dos elementos que levaram a essa conjuntura [You are probably correct about avoiding some elements. In Post-Soviet Russia Boulgakov’s name has become a kind of trademark supporting many commercial events. Referring to one of them, a good friend of mine said: "Bulgakov wrote "The Master and Margarita" when he was ill, an outlaw, and banned by officials, and now they are throwing parties in swimmingpools filled with Champagne…" He expressed feelings that are shared by many Boulgakov's readers . I put it into consideration when I started to work on the script, and tried to avoid a “commercialized” approach of adapting it.] (se bem que os mesmos fariam hoje menos furor, diga-se de passagem; o tratamento de Cristo e de Pilatos, depois de tanta banalização mediática, já impede de pensar no papel dessas duas figuras históricas e nas possibilidades de interpretação histórica). Pelo contrário, talvez graças à já passada queda do bloco soviético, às novas liberdades entretanto conquistadas, os autores optam por sublinhar os aspectos mais histriónicos e sardónicos que Boulgakov aponta à sua então contemporânea sociedade (estamos no tempo de Estaline, e Boulgakov não é um alinhado à cultura oficial, como muitos outros autores russos da época), gozando portanto a liberdade possível hoje para lançar um olhar sobre o passado. [In general, I think, you are right. The script was based on the uncensored version, and additional sources. Bulgakov left a great deal of manuscripts. He had been working on the novel until his final days. By different sources, he had written from six to eight variants. I have studied the available part of them. It allowed to understand which ideas and episodes were the most significant for the writer - those ones that traveled from manuscript to manuscript. According to Bulgakov's diary, an impulse for the novel made the anti-religious campaign of the 20's. A son of an orthodox theologian, he hadn't been a true believer, but was shocked by the fanatic madness of godfighters. As a result, he established parallels with the crucifixion, and got strong feeling that contemporary events were repeating the events that destroyed the ancient and highly civilized world. Moscow seemed to be the next Rome, and the Devil was coming to witness its falling. Later the text acquired additional ideas, reflected some of the events from the writer's life, and finally turned into his main and very personal creation. In order to pass censorship, Bulgakov didn't clarify his parallels, and used allegories (such as the psychiatric hospital instead of a prison). The idea about the next Rome was smoothed, but it remained the driving force of the plot.] Os episódios de Pilatos estão presentes, claro, mas precisamente as partes que servem para sublinhar a estranha relação de poderes entre Cristo e Deus, Cristo e Pilatos, Pilatos e Tibério, ecoando ou servindo de metáfora em relação aos poderes da União Soviética.

Por outro lado, como um baixo contínuo, está também inerente a ironia com que se retrata a população russa, a qual, não obstante a tentativa de “educação” estatal, continuava a ser uma população de supersticiosos, um povo sem verniz, de raízes rurais e lentos às potencialidades da expressão mais pessoal (muito parecidos connosco nesses aspectos): a entrada do Diabo, Woland, por cá “o Mafarrico” , na cidade de Moscovo, apenas acelera a destruição da patina dessa falsa educação, terminando no incêndio da cidade... Todavia, em vez desse incêndio servir de apocalipse final, e espoletar os quatro cavaleiros no seu derradeiro encargo, acaba por levar a mais uma rusga policial mal-enjorcada. [Boulgakov kept the apocalypse in mind and in drafts, but the final fire was not depicted properly in the published in 1967 version. Otherwise censorship would not approve the edition.] Enfim, de uma maneira ou de outra, tudo concorre para uma só finalidade: um gozo total sobre uma sociedade sem rumo. Nessa conjuntura, o amor entre o escritor do manuscrito e a mulher que o ama incondicionalmente, o eco invertido do mito de Fausto, e que dá título ao livro, acaba por se tornar quase uma nota secundária. [You have made interesting, keen notes. Comparing the Boulgakov's structure of the novel with ours could help to enlighten specifics of our adaptation. Originally, "The Master and Margarita" is constructed from three major lines. The main line goes from the beginning to the end, and tells about the Devil’s appearance in the Moscow of the 20's and 30's, and the following after those events. They were depicted by Bulgakov sometimes in a realistic manner, some other times in a satiric manner, sometimes in a phantasmagoric manner. The second line tells a story of love between a woman and the master, a historian, who writes and publishes a novel about Pontius Pilate. Considering the gory, brutal anti-religious campaigns of those times, their destiny must be fated (by the way, my mother's grandfather, a country orthodox priest, was murdered by local activists in one of those campaigns). The heroes become victims of the betrayal. Almost all Bulgakov's books and plays have good endings. The reality of the 30's did not suggest too many opportunities for that. Therefore, unreal forces come to help the lovers. The line with the master and Margarita crosses the first one, and they go together in the second half of the novel. The third line is the master's novel by itself. A story of crucifixion is written from the point of view of the Romanian governor-general in Jerusalem. It is continuously inserted part by part along the two other lines, and seems independent of them, but the novel about Pontius Pilate supports the general parallel between post-revolutionary Moscow and ancient Rome. The multiplicity of lines complicates every adaptation, independently of the genre. A creator of an adaptation of The Master and Margarita for the screen, or for the theatre, or any for any other medium has to solve this problem first. Considering the limitations of the comic genre, I've found this solution: the graphic adaptation consists of the introduction, three chapters, and the conclusion. The introduction and the 1st chapter, "The Variety", retell the appearance of the Devil in Moscow, and his activity, culminated during a show at the Variety Theatre. They follow the sequence of the corresponding part of Bulgakov's text as well as the 3rd part, "The Ball", and the conclusion do. Substantial changes were done in the structure of the chapter "Pilate". It became compressed within the margins of the master's conversation with his neighbor-poet at the psychiatric hospital. As you mentioned, the second line really became the secondary. In fact, the reason for this is in the particular nature of the line. The story of love between the master and Margarita reflects events in the Boulgakov’s life. That awareness obliged us to treat the romantic part of the story accurately and guardedly. You have exactly described the results, and we are not upset about them. They were intentional and elaborated.]

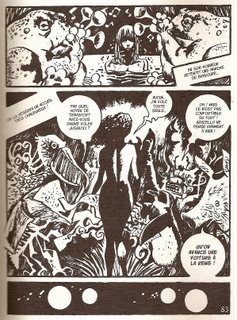

Por outro lado, como um baixo contínuo, está também inerente a ironia com que se retrata a população russa, a qual, não obstante a tentativa de “educação” estatal, continuava a ser uma população de supersticiosos, um povo sem verniz, de raízes rurais e lentos às potencialidades da expressão mais pessoal (muito parecidos connosco nesses aspectos): a entrada do Diabo, Woland, por cá “o Mafarrico” , na cidade de Moscovo, apenas acelera a destruição da patina dessa falsa educação, terminando no incêndio da cidade... Todavia, em vez desse incêndio servir de apocalipse final, e espoletar os quatro cavaleiros no seu derradeiro encargo, acaba por levar a mais uma rusga policial mal-enjorcada. [Boulgakov kept the apocalypse in mind and in drafts, but the final fire was not depicted properly in the published in 1967 version. Otherwise censorship would not approve the edition.] Enfim, de uma maneira ou de outra, tudo concorre para uma só finalidade: um gozo total sobre uma sociedade sem rumo. Nessa conjuntura, o amor entre o escritor do manuscrito e a mulher que o ama incondicionalmente, o eco invertido do mito de Fausto, e que dá título ao livro, acaba por se tornar quase uma nota secundária. [You have made interesting, keen notes. Comparing the Boulgakov's structure of the novel with ours could help to enlighten specifics of our adaptation. Originally, "The Master and Margarita" is constructed from three major lines. The main line goes from the beginning to the end, and tells about the Devil’s appearance in the Moscow of the 20's and 30's, and the following after those events. They were depicted by Bulgakov sometimes in a realistic manner, some other times in a satiric manner, sometimes in a phantasmagoric manner. The second line tells a story of love between a woman and the master, a historian, who writes and publishes a novel about Pontius Pilate. Considering the gory, brutal anti-religious campaigns of those times, their destiny must be fated (by the way, my mother's grandfather, a country orthodox priest, was murdered by local activists in one of those campaigns). The heroes become victims of the betrayal. Almost all Bulgakov's books and plays have good endings. The reality of the 30's did not suggest too many opportunities for that. Therefore, unreal forces come to help the lovers. The line with the master and Margarita crosses the first one, and they go together in the second half of the novel. The third line is the master's novel by itself. A story of crucifixion is written from the point of view of the Romanian governor-general in Jerusalem. It is continuously inserted part by part along the two other lines, and seems independent of them, but the novel about Pontius Pilate supports the general parallel between post-revolutionary Moscow and ancient Rome. The multiplicity of lines complicates every adaptation, independently of the genre. A creator of an adaptation of The Master and Margarita for the screen, or for the theatre, or any for any other medium has to solve this problem first. Considering the limitations of the comic genre, I've found this solution: the graphic adaptation consists of the introduction, three chapters, and the conclusion. The introduction and the 1st chapter, "The Variety", retell the appearance of the Devil in Moscow, and his activity, culminated during a show at the Variety Theatre. They follow the sequence of the corresponding part of Bulgakov's text as well as the 3rd part, "The Ball", and the conclusion do. Substantial changes were done in the structure of the chapter "Pilate". It became compressed within the margins of the master's conversation with his neighbor-poet at the psychiatric hospital. As you mentioned, the second line really became the secondary. In fact, the reason for this is in the particular nature of the line. The story of love between the master and Margarita reflects events in the Boulgakov’s life. That awareness obliged us to treat the romantic part of the story accurately and guardedly. You have exactly described the results, and we are not upset about them. They were intentional and elaborated.]O trabalho de Zaslavsky e Akishine não encerra grandes surpresas em relação ao uso da linguagem “clássica” (os elementos, os modelos, as estratégias), mas deve ser anotada a integração das tais tradições russas particulares: um cartaz de agitprop aqui, as ilustrações de um Lebedev ali, uma relação com as onomatopeias das canções, das exclamações ou doutras fontes de som que recorda o futurismo russo. [I believe Askold’s art did have some genuine surprises like transferring panels with the star blending into the bat (and visa versa) and many others. On the other hand, 15 years passed from the creation of our graphic adaptation. Since that, the language of visual storytelling has progressed.] A cena de Margarida no baile, introduzida pela prancha aqui apresentada, é o grande auge desta obra, obviamente, onde se cruzam todas as personagens, onde convergem todas as criaturas fantásticas, onde se resolvem todas as crises. E é curioso como, em relação a outros episódios anteriores, os autores exercem aqui alguma contenção formal. Por um lado, servirá para sublinhar o facto de que os verdadeiros vitoriosos, enfim, de todo o ataque de Woland sobre Moscovo, são de facto as personagens mais humildes e apagadas: Margarida e o Mestre. Por outro, é como se o faz-de-conta do baile – a cena mais fabulosa – apagasse o faz-de-conta que os autores empregam para os episódios mais “realistas”. Uma questão de equilíbrio interno, talvez. [Interesting observations as well. The page chosen by you for displaying was really intended to indicate a border between the real claustrophobic world of the 30's and the fantastic world. Does realism of the ball controvert the realism of the conclusion? As an involved in the creation person, I am barely able to judge that :) Thank you again for your excellent review!

Misha Zaslavskiy]

About the authors of the Boulgakov's adaptation [by Misha Zaslavskiy]:I worked on textual adaptation and a script for comics.Askold Akishin is the artist of the graphic novel. Below is his brief bio. Where it is possible, I added links to previews of respective comics:Askold Akishine (b. 1965, Moscow) is a one of most prolific Russian creators of comics. After being discharging from the Army, he joined the Moscow comics-club KOM, and participated in its editions. After folding the club in 1993, Akishine has contributed for numerous book publishers, magazines and newspapers.Among his main works are:War Chronicles (1990), a graphic adaptation of E.M. Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front; Georgy Zhukov (1990-1991), a biographical comic about the legendary Soviet Marshal; The Russian Tsars (1991), a graphic novel depicting the history of Russian Monarchy; The Master & Margarita (1993, later on published in 2005 in France by Actes Sud), a graphic adaptation of the Mikhail Boulgakov novel;

Moscow Marathon (1998), a continuous newspaper strip based on a crime fiction story; Isotope-13: The Bad Association (2003), a continuous newspaper horror strip;

Tales of the Future (2003), a collection of "underground" strips; The Pioneer Truth: Horror (2004-2005), a huge collection of comics based on childish scary stories from the school folklore of the 80's; Temple, City, Dreams (2005), a graphic adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft's stories.

Akishine's creative interests lie in horror and historical subjects. http://www.comics.aha.ru/rus/caley/

http://www.comics.aha.ru/rus/dead/

http://www.comics.aha.ru/rus/cave/

http://www.comics.aha.ru/rus/esher3/

http://www.comics.aha.ru/rus/mars/

On the International Moscow Festival of Comics, The Pioneer Truth: Horror received a Grand Scenario in 2005, and the Grand Prix in 2007.

Eu Pedro Miguel da Silva Moura, DEIXO EM TESTAMENTO àqueles a quem Deus concedeu a iluminação e o poder de promoção da leitura de banda desenhada (leia-se à Bedeteca de Lisboa) todas as obras constantes neste blogue.

ResponderEliminarPor acaso, meu caro, a minha ideia é queimar todos os livros junto ao meu corpo, misturar as cinzas e mandar fazer lápis # 3 com elas, os quais serão distribuídos depois por um reduzido grupo de eleitos... Mas se houver contrapartidas financeiras desde já dessa instituição, posso ainda rever o dito documento junto ao meu advogado.

ResponderEliminarUm bem-haja,

Pedro António Sequeira Lopes da Cunha e Freire Moura, o 3º

eu pelo meu lado tenho essa BD. Foi uma amiga muito especial que me deu... por isso o "brevemente" só faz sentido se vier uma edição portuguesa, o que claro que não me parece que irá acontecer. Já podia era vir o vol.3 do Sandman... sempre a espera que as coisas aconteçam em Portugal......... (.)

ResponderEliminarEste último comentário é um pouco críptico. O meu "brevemente" significa que farei um texto sobre o livro daqui a pouco tempo. Se ele vier a ser editado ou não em português é-me indiferente, já que não o creio, nem as editoras mostram grandes rasgos desse tipo. Se eu me cingisse às edições em português das grandes editoras, estava calado.

ResponderEliminarQuanto ao terceiro volume do Sandman, por acaso posso dar uma "insider information": 'tá quase!

"Master I Margarita", de Bulgakov, é um excelente romance! Desconhecia esta adaptação em BD, mas, sob uma rápida observação, tenho de dizer que as personagens da capa estão bem diferentes daquilo que imaginei durante a leitura da obra que lhe serve de molde. De qualquer das maneiras, é sempre bom saber que as boas obras provocam outras.

ResponderEliminarCheers!

Estava equivocado quanto ao sujeito do "brevemente". Sendo assim as minhas desculpas. Inocência a minha pensar que iria haver uma edição em português de "Le Maître & Marguerite", mas apesar de tudo é sinal que ainda acredito no país.

ResponderEliminarCaro René Alan,

ResponderEliminarnão há que pedir desculpas, foi só um mal-entendido. É pena, de facto, que não possamos pensar em mais edições destas em português (cá, pelo menos).

Seja como for, o romance de Boulgakov está disponível, até na colecção do Público (Mil Folhas?) - passo a publicidade. Pelo menos essa leitura é para já obrigatória...

Abraços,

Pedro